How can historians and social scientists make sense of a phenomenon that is mostly described having no past and as just emerging? Shouldn’t the Citizen Sciences, DIYbio and the Maker-Scene be simply left those doing and living it – to all the geeks, nerds, and active citizens out there claiming their right to participate in the production of scientific knowledge? Is it already useful or possible to reflect on their quest to redefine the boundaries between experts and amateurs? Can we connect these movement to the broader issues of professionalization and participation, which are not restricted to the popular figure of the amateur field naturalist? And if so: What would it mean to rethink science and public participation for, both, us as academics reflecting on this transformation in the this history of science, as well as for those citizens striving for participation?

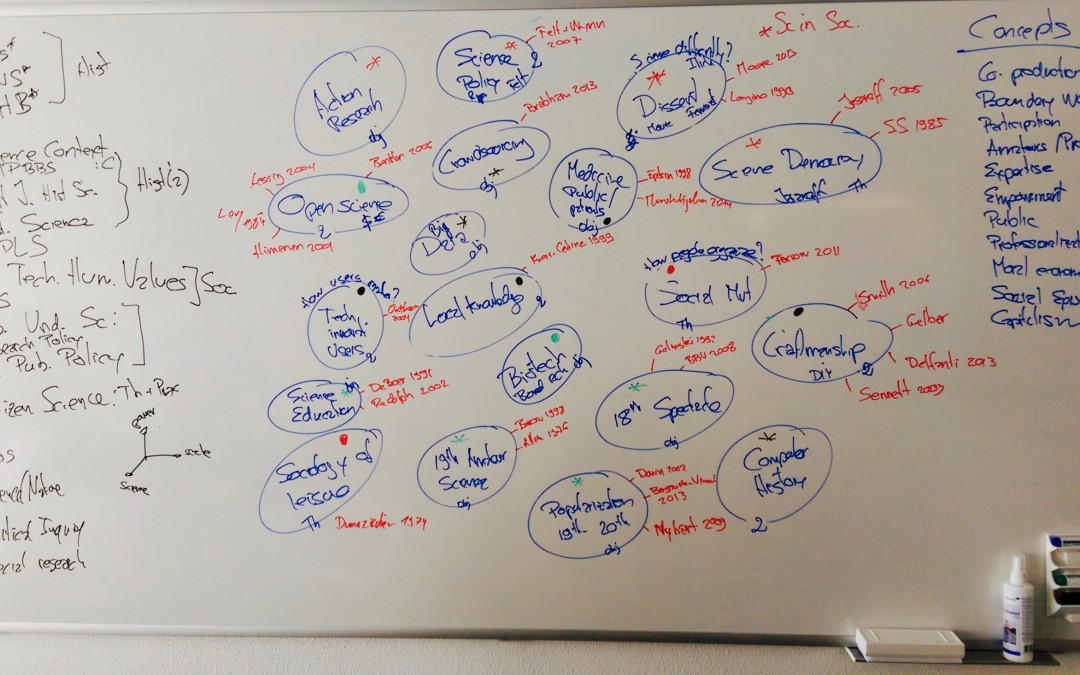

A first step to approach this complex questions is to identify the scholarly fields in which public participation in science (broadly construed) has been addressed within the last decades. Interesting are in particular their (historically contingent) motives and their foci / topics. Therefore, during the first week of our team work, we charted the wide plains of activities and literature reflecting on public participation in science on different levels.

During the mapping process, we identified the following areas of research and (political) engagement in which public participation in science played (or still plays) a role:

- scientific dissent (20th century)

- science, performance, and spectacle (18th century)

- amateur/popular science (19th and 20th century )

- popularization of science (19th and 20th century)

- action research (20th century)

- science and democracy discourse

- science policy and governance

- sociology of expertise expertise

- sociology of leisure

- science education

- craftsmanship

- social movements theory

- participation in (bio)medicine

- technological innovation

- open science

- local knowledge cultures

- computer history

- big data studies

We are currently exploring these fields (and more) during our reading seminars. We will also create a literature-database and bibliographies, as part of our exploration, which will be made public.

In addition we defined a preliminary bibliography of twelve monographs and edited volumes which, in our opinion, constitute essential readings for anyone interested in understanding the the transformations of public participation in science:

- Chilvers, Jason, and Matthew Kearnes (Eds). Remaking Participation: Science, Environment and Emergent Publics. Abingdon, Oxon : Routledge, 2016.

- Moore, Kelly. Disrupting Science: Social Movements, American Scientists, and the Politics of the Military, 1945-1975. Princeton studies in cultural sociology. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2008.

- Irwin, Alan. Citizen Science: a Study of People, Expertise, and Sustainable Development. Environment and society. London ; New York: Routledge, 1995.

- Epstein, Steven. Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. Bd. 7. Univ of California Press, 1996.

- Delfanti, Alessandro. Biohackers: The Politics of Open Science. Pluto Press, 2013.

- Turner, Fred. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the rise of digital utopianism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

- Bowler, Peter J. Science for all: the popularization of science in early twentieth-century Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

- Collins, Harry M. Are We All Scientific Experts Now? New Human Frontiers Series. Cambridge: Polity, 2014.

- Brabham, Daren C. Crowdsourcing. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2013.

- Jasanoff, Sheila. States of Knowledge : The Co-Production of Science and Social Order. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Himanen, Pekka. The Hacker Ethic. A Radical Approach to the Philosophy of Business. Random House Trade Paperbacks, 2002.

- Maasen, Sabine, and Peter Weingart (Eds), Democratization of expertise?: exploring novel forms of scientific advice in political decision-making. Sociology of the sciences : a yearbook. Dordrecht ; London: Springer, 2008.

What would your list look like? Can you suggest other essential readings on this theme? Let’s make a participatory bibliography!

DM

Dear Rethinking Science – team,

With much interest we took notice of your project. We will certainly continue to follow you. One remark for now: Most knowledge we hope to have in the social and political sciences is based on common-sense notions of lay people. We make these notions a bit more consistent and coherent, and we collect some more empirical support in a more systematic way, but the origins most of the time are lay people. Sometimes we come up with some hypotheses and ideas of our own, and often these have to be corrected by “lay” people, testing these hypotheses and ideas in actual practice. We cannot do without lay people. The scholar who demonstrated this consistently in his work and who we definitely missed in your bibliography is Charles E. Lindblom. See among others: “The science of muddling through” (1959), Usable Knowledge (1979) and Inquiry and Change (1990). In our own project, Social Science Works, we are much influenced by Lindblom. We further public participation in social and political science by (1) helping citizens to understand and, at the same time, to control social research and by (2) promoting a more socially relevant social science that is more oriented to problems and less to theories and methods. We believe that real progress in our disciplines depends heavily on public participation. So we look forward to the progress of your project!

With best wishes,

Hans Blokland / Social Science Works

Dear Hans,

thank you so much for reading our blog. I think you’re right when you say that a lot of knowledge in the humanities and the social sciences depends on the common-sense of everyday experience. But I also believe that this “lay-expertise” is increasingly spreading to other fields. Within my own research I experienced that (for example) genetic knowledge is to a large extent a product of translation processes between “laymen” (patients and their families) and “experts” (medical professionals and scientists) and that the boundaries between those two categories get increasingly blurred.

About your reading suggestions: The theory of Incrementalism in policy and decision-making of Lindblom seems to be very interesting and helpful for our endeavour! I just ordered “Usable knowledge: social science and social problem solving” and I’m looking forward to read it.

Very best wishes,

Dana Mahr